Parallels: Move forward by looking back

Looking back in history could help the present generation become aware and vigilant.

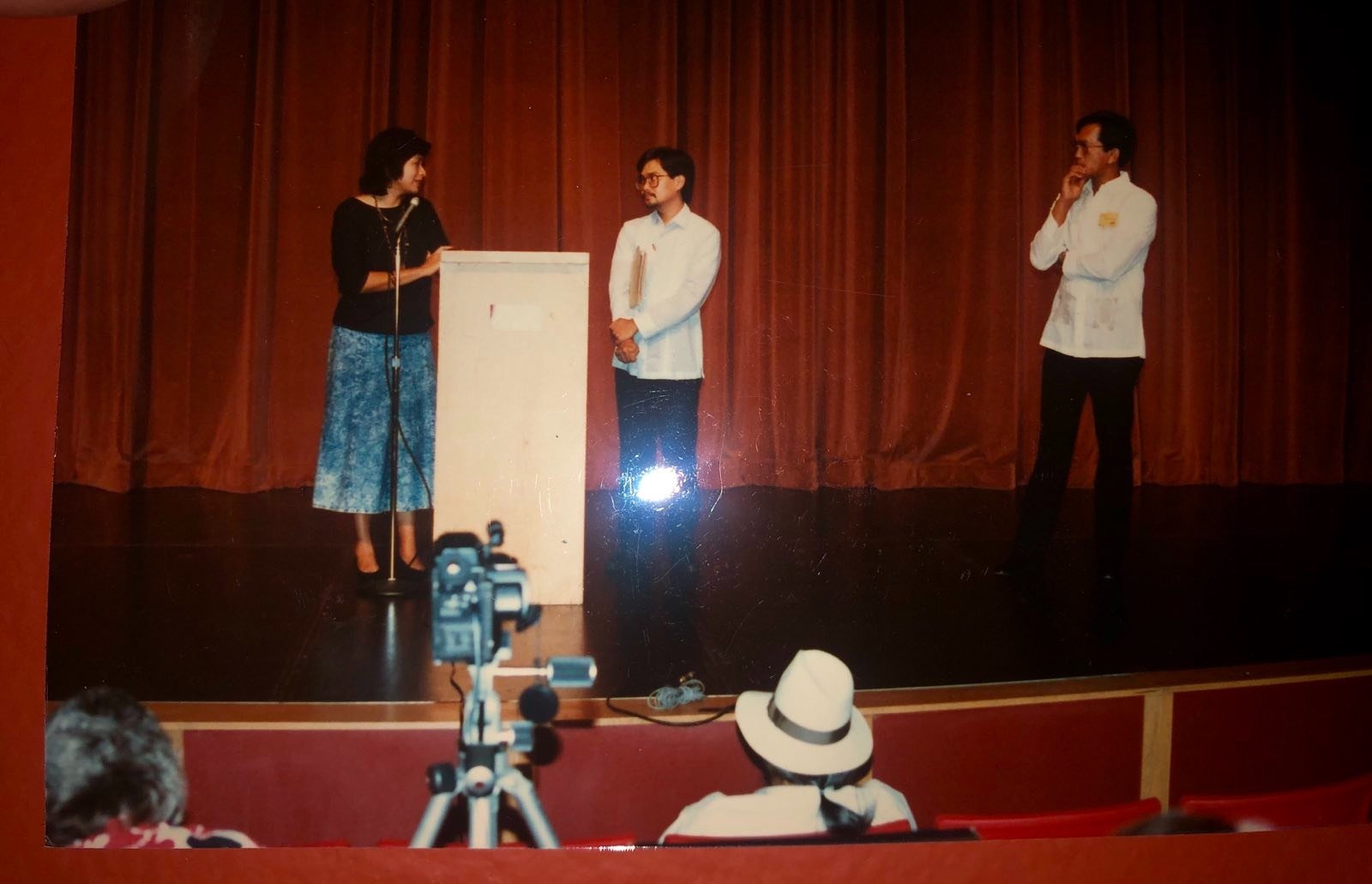

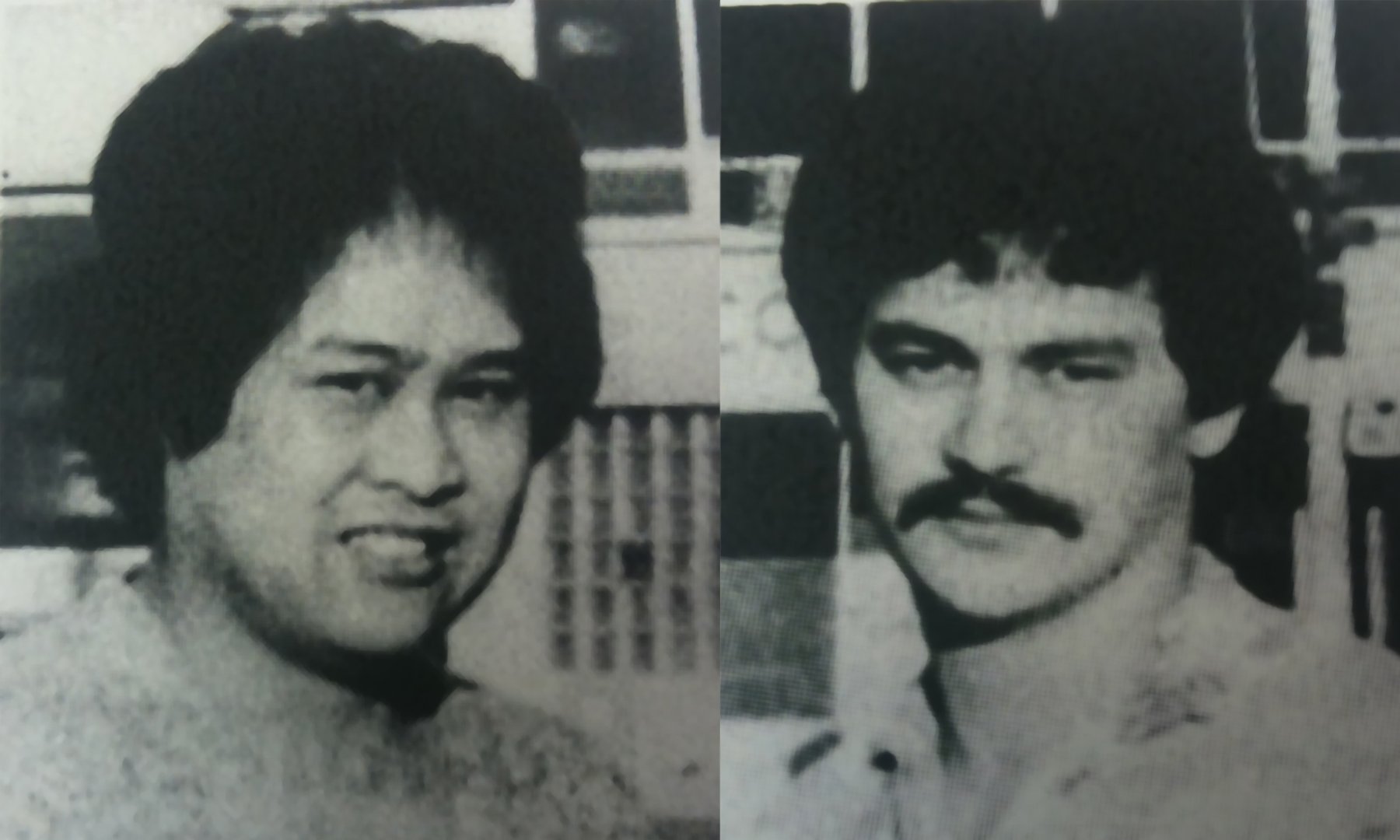

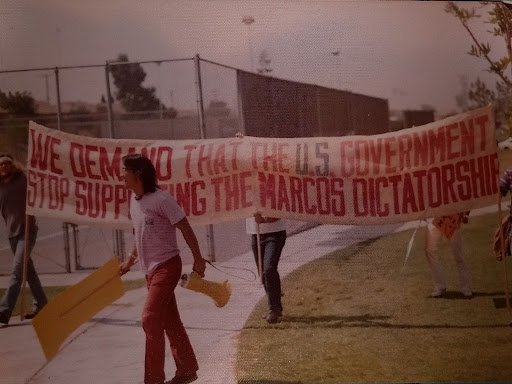

Survivors of Martial Law Years: Rick Esguerra of the Philippine Solidarity Group and Ed Muyot of Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship

The Anti-Dictatorship Movement of Filipino-Americans is a crucial component of Fil-Am History that is usually left out of the conversation.

In a time of rising fascism at home and around the world, it is high time that this part of our history be shared and discussed. Especially when there are so many similarities to then and now.

Nature of Marcos and Duterte anti-people policies

Both Ferdinand Marcos and Rodrigo Duterte have invested in “Build, Build, Build” projects that create airports, seaports, and infrastructure projects, purportedly for the Filipino People, but in reality only serve to attract foreign investors and facilitate the exchange of capital. During Marcos’ era, these infrastructure projects included identifying more than 40 mining operations (often at the expense of seizing Indigenous ancestral lands), exporting raw materials and natural resources, building 25 airports… Now, in Duterte’s regime, the “Build, Build, Build” platform’s primary example is the dumping of dolomite sand onto the Manila Bay, purportedly to help alleviate the mental health stress of the Filipino People, in spite of experts’ and scientists’ opinions. This signals the misaligned priorities of the Duterte administration, in a country that has had the longest COVID-19 lockdown in Southeast Asia.

Both Marcos and Duterte have borrowed huge sums of money from foreign banks, allegedly to go to these infrastructure projects. Later on, however, government audits have revealed how both administrations facilitated the theft of billions and concealment of missing funds. The Philippine Commission on Good Government (PCGG), established by the late president Cory Aquino, holds and investigates records of the Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth, while lately, the Duterte administration’s links with Pharmally is under probe in the Senate, to investigate the COVID-19 funds that have been “mismanaged.”

Both Marcos and Duterte claim to commit to establishing “peace and order,” which is code for suppressing any and all dissent using the police and military force. Both are concerned, not with “external aggression” (like, say, the U.S. and China infringement on the Philippines’ sovereignty), but more with “internal subversion” (targeting the Huks during Marcos’ era and implementing the Anti-Terror Law and mobilizing the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict [NTF-ELCAC] that aim to “clear communist rebels” during Duterte’s regime). Furthermore, in the name of “peace and order,” at least 9,000 human rights violations were committed during Marcos’ Martial Law, while 20,000 have been murdered amidst Duterte’s War on Drugs.

Mobilizing both the impulse for constructing infrastructure projects and creating a need for “peace and order,” both Marcos and Duterte claim to be building the Philippines as a nation. But for whom?

repression and red tagging

“It is believed that Domingo and Viernes leading members of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP) and active in the Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship were shot to death because of their anti-Marcos views. A month prior to their deaths, they successfully advocated during the ILWU's convention in Honolulu for a union delegation to go to the Philippines and look into charges of union repression by . . . Marcos government.”

Historically, the U.S. government has seen Philippine communists as threatening, with the way that Philippine communists have theorized and linked capitalism and imperialism and interrogated the United States of America “as part of the oppressive world-wide system of white colonial rule over non-white peoples.” The fascist dictators of the Philippine government have been puppets of the U.S. regime – Ferdinand Marcos then and Rodrigo Duterte now – and eerily, both ordered “to liquidate [the] Communist apparatus” back in the 1970s and ordered “the military to destroy the [communist] apparatus” in the present. This “anti-red” politics has functioned to limit what is considered “acceptable” political activity in the Philippines.

Jersey City, NJ 2021

Woodside, NY 2021

Philippine Consulate sponsored red tagging and black propaganda activities against activists of Malaya Movement and various progressive Filipino groups.

lobbying to end US support for

the philippine government

Resistance on the legislative front is a part of our long history of struggle against dictators. Similar to Filipino American-led legislative advocacy working to pass the Philippine Human Rights Act (PHRA, a bill to suspend U.S. security assistance to the Philippines until human rights violations cease), Filipino American activists lobbied to end U.S. support for the Philippines government through the 1970s and 1980s.

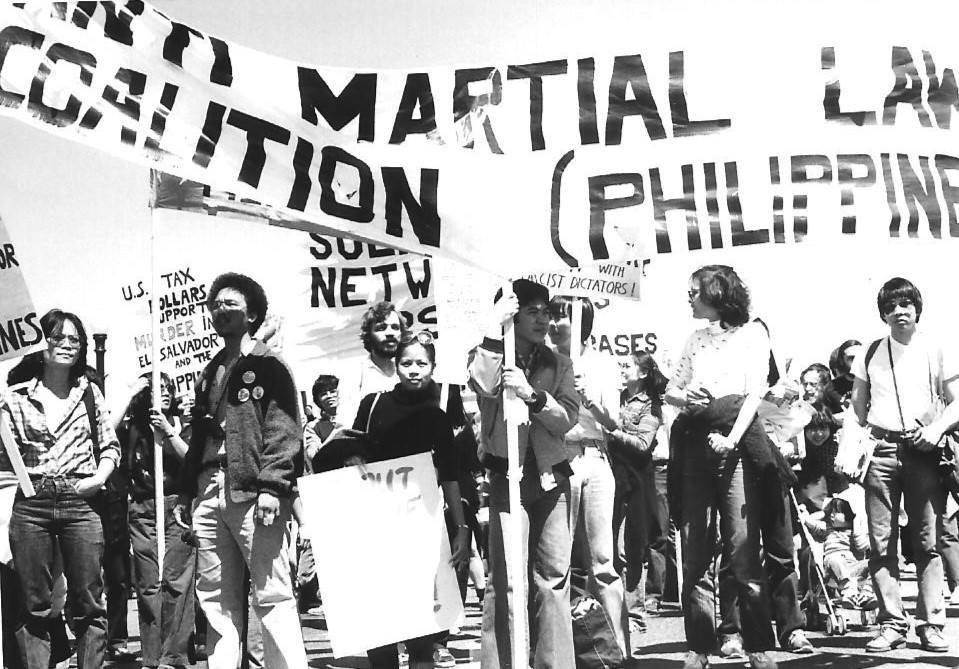

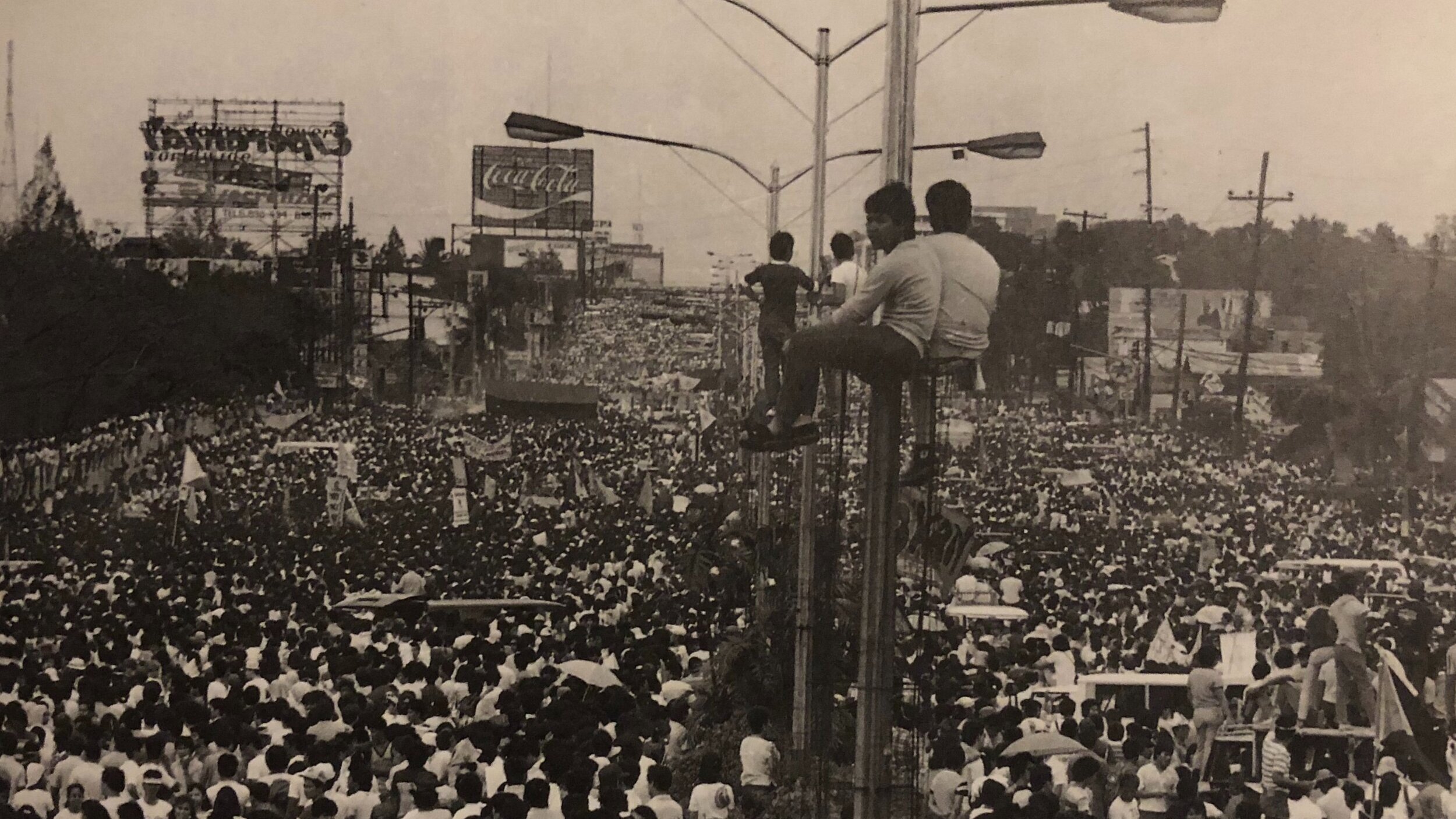

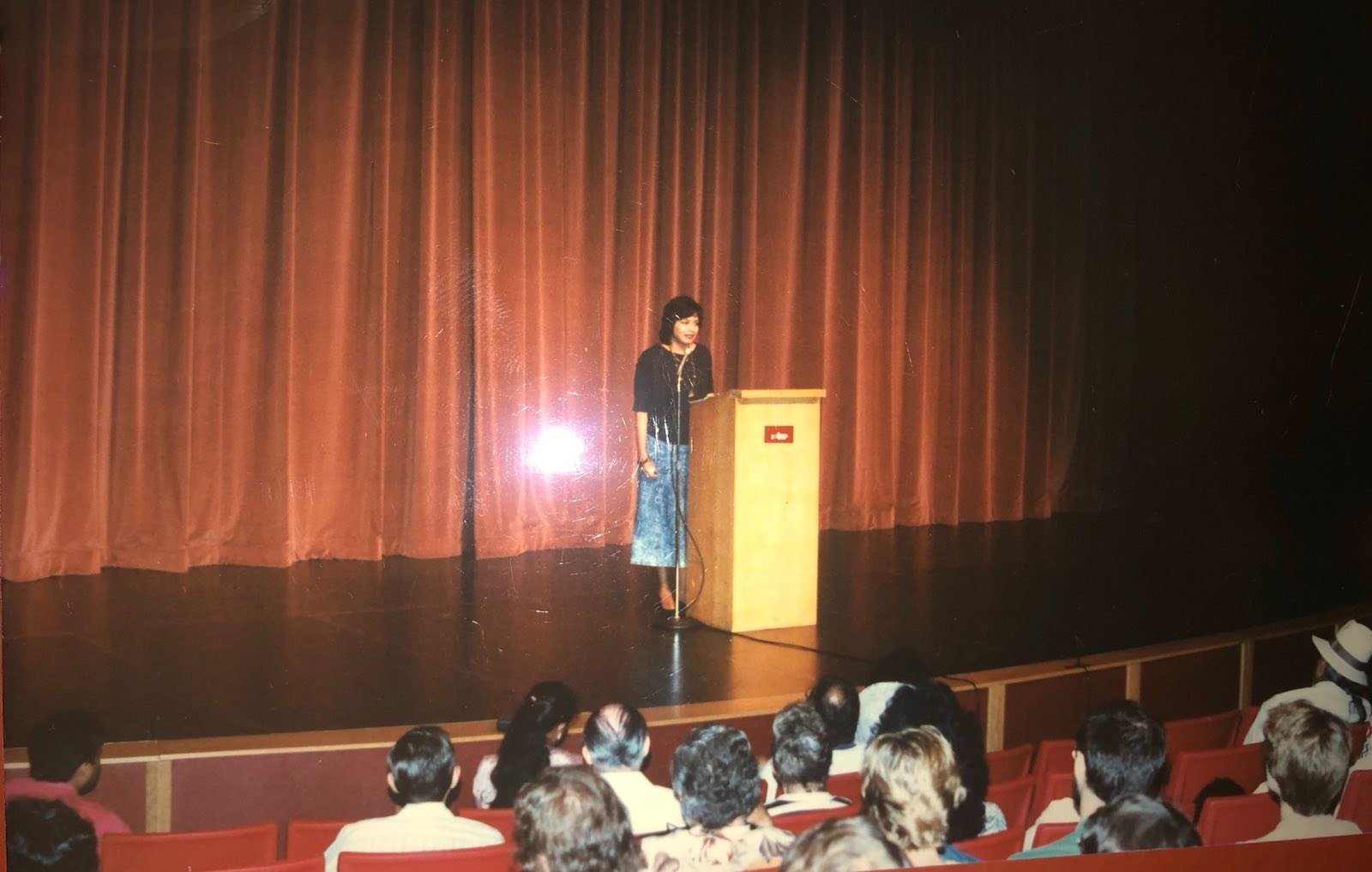

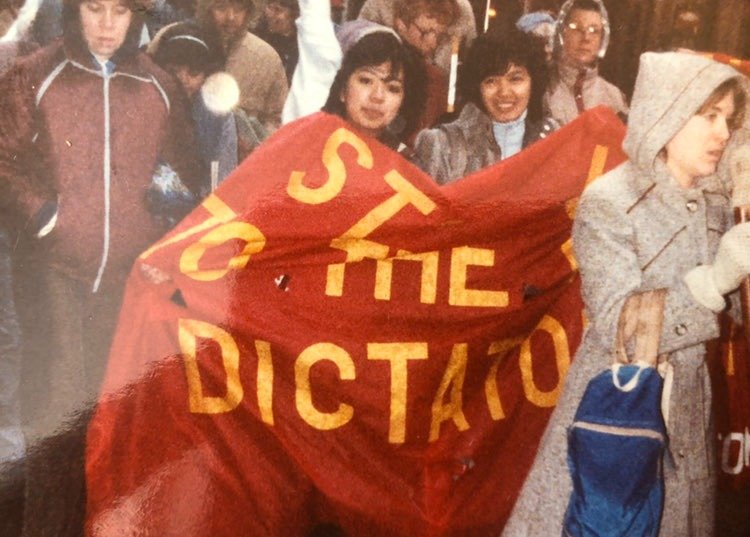

Inspired by the Civil Rights era and anti-Vietnam War struggles, activists from the Movement for a Free Philippines (MFP) fought to cut U.S. military assistance to the Marcos dictatorship by protesting and lobbying in Washington DC and activists from the Union of Democratic Filipinos (Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, KDP) successfully lobbied against an extradition treaty for Marcos in light of embezzlement charges against Marcos. Filipino activists and organizers joined the Anti-Martial Law Coalition, which later became the Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship (CAMD). With ending U.S. aid as its main goal, CAMD held frequent picket line protests in front of Philippine consulates where they often chanted “Stop U.S. aid to the Marcos regime!” and focused on mass education in the U.S.

Today, Filipinos in the U.S. continue to struggle to defend the freedom, human rights and sovereignty of the Filipino people. In 2019, Malaya Movement USA organized a National Summit to learn, build community, strategize, and take action with fellow Filipino activist organizations and solidarity allies in Washington DC. On April 8, 2019, Filipino Americans and allies came together and conducted a die-in protest at the US Senate Hart Building to demand the end of US support to the Duterte regime. Since then, Filipino Americans have supported lobbying and phone-banking efforts and organized protests like the annual People’s State of the Union Address to gain the American public’s support in ending the human rights violations instigated by the Duterte regime. As of October 2021, our community has been able to get 22 Congress representatives to co-sponsor the PHRA.

Protests, Cultural work

Protests and cultural work represent the many methods of political expression and resistance in the Filipino diaspora. For example, in 1976 the KDP released a record,“Philippines Bangon! Arise!” which is a collection of revolutionary songs from the Philippines. Political prisoner poetry gained international recognition and served as a link to other social movements. Thanks to the lobbying work of her sister, Dr. Delia Aguilar, Mila D. Aguilar’s political prisoner poetry reached a U.S. audience. Aguilar’s A Comrade is as Precious as a Rice Seedling. was published in the U.S. in 1987 by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, with an introduction by leading Black feminist, Audre Lorde.

“Regularized activities like annual protests on the anniversary of martial law, Christmas caroling, community forums, annual conferences, and mass distribution of the Taliba newsletter kept the controversy over martial law alive in the Filipino community and general public during periods of low political activity (‘ebbs’) around the Philippines.”

multiplicity and coalition of organizations

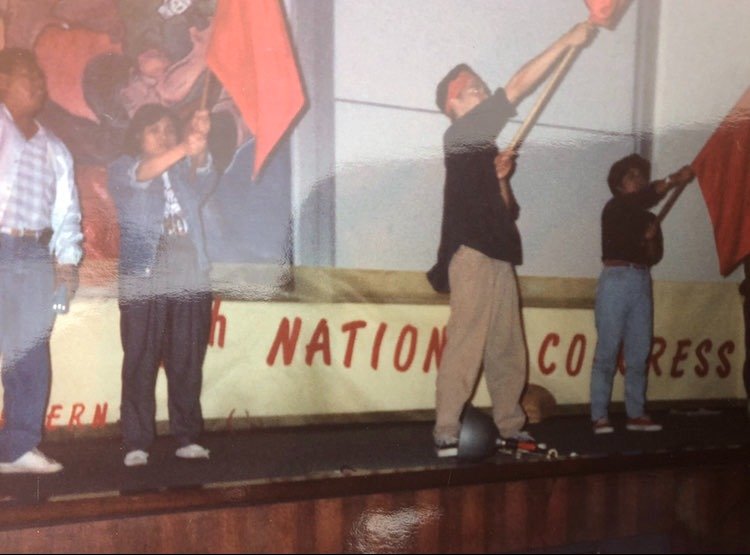

The MFP, KDP, NAM and CAMD united on the demand to stop all U.S. support for Marcos and backed Aquino’s anti-fascist and largely liberal democratic platform.

solidarity with non-Filipino organizations

The Coalition Against the Marcos Dictatorship (CAMD) and the Philippine Solidarity Network had been present at the conference for Jesse Jackson, an American activist and politician in Montreal.

WE must learn from history and use the lessons to move forward as we continue to struggle for social change in the Philippines.

Join the movement

Sources & references:

Patty Rivera, “Toronto: PH Martial Law Survivors Recall the Years of Living Dangerously,” Inquirer, September 25, 2019, par. 5.

Philippine News Agency, “‘Build, Build, Build’ delivers, sets up infra for future,” 2021.

Guzman, R. “What Build Build Build has delivered,” 2021.

Marcos, F. “Third State of the Nation Address,” 1968.

Davies, N. “The $10bn question: what happened to the Marcos millions?” 2016.

Punzalan, J. “Robredo: Curbing pandemic best for mental health, not white sand,” 2020.

Marcos, F. “Third State of the Nation Address,” 1968.

Romero, P. “‘NTF-ELCAC charging administrative expenses to agencies’,” 2021.

Regencia, T. “Senator: Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war has killed 20,000,” 2018.

ABS-CBN News, “BY THE NUMBERS: Human rights violations during Marcos' rule,” 2018.

Kovacs, B. A., & Lynch, T. “Is Duterte ‘Nation-Building’ in the Philippines?,” 2016.

“Viernes, Gene Allen.” Bantayog ng mga Bayani, October 5, 2015.

“Domingo, Silme Garciano.” Bantayog ng mga Bayani, October 5, 2015.

Gabby Gomez, “Philippine Agents Harass and Spy on Martial Law Opponents in U.S.,” International Examiner, September 7, 1983, par. 9.

Colleen Woods, “Seditious Crimes and Rebellious Conspiracies: Anti-communism and US Empire in the Philippines,” Journal of Contemporary History 53, no. 1 (2018): 62-3.

Jose V. Fuentecilla, Fighting from a Distance: How Filipino Exiles Helped Topple a Dictator, University of Illinois Press, 2013, 1.

Gwertzman, B. Feb. 25, 1986. New York Times.

Manglapus, R. 1983. Retrieved from: Video of Raul Manglapus speech in 1983 in Washington, DC

Pimintel, B. October 3, 2017. Inquirer News.

Pimentel, B. September 18, 2012. Inquirer News.

Congress.gov, Philippine Human Rights Act.

Bello & Reyes, info on ending US aid...

Helen C. Toribio, “We are Revolution: A Reflective History of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP),” Amerasia Journal 24, no. 2 (1998): 171.

Protest photos from Felix Tuyay (former KDP in San Diego)

VOX Media: International Hotel video

“We Are Revolution: A Reflective History of the Union of Democratic FIlipinos” by Helen C. Toribio

A Time to Rise: Collective Memoirs of the Union of Democratic Filipinos

Madge Bello and Vincent Reyes, "Filipino Americans and the Marcos Overthrow: The Transformation of Political Consciousness," Amerasia Journal 13, no. 1 (1986): 78.

Madge Bello and Vincent Reyes, "Filipino Americans and the Marcos Overthrow: The Transformation of Political Consciousness," Amerasia Journal 13, no. 1 (1986): 81.

“Jesse Jackson, activiste et politicien américain, à Montréal le 9 septembre 1984,” La Vitrine des Archives de BAnQ, September 9, 2015, par. 4.